The Tunguska Event, 1908

|

| Location of Tunguska Event. © Bobby D. Bryant/Wikimedia Commons |

You feel like you're on fire, too. Your shirt is so hot that you go to tear it off, fearing it will ignite. But then, just as suddenly, the sky snaps shut. You hear a loud boom as you're thrown from your chair and land a few yards away. Briefly, you black out, and when you regain consciousness, you feel the earth shaking, and a continuous barrage of noise, as though rocks are falling or cannons are being fired, repeatedly.

When the noise ends, you look around, gingerly. You see a wide swath has been cut through the grass between the houses, as though it was burned when the hot air rushed through. Some of your crops have been damaged. The iron lock on your barn snapped. Many of the windows have shattered.

The Event

This is exactly what happened to S. Semenov on the day of the Tunguska Event. He reported it, in 1921, to an expedition led by Leonid Kulik. Mr. Semenov was about 25 miles away from the center of the blast.Others reported similar stories. The noise was intense. The light was blinding. The heat was incredible, and swept over them in intense winds coming from the north.

The Kulik Expedition

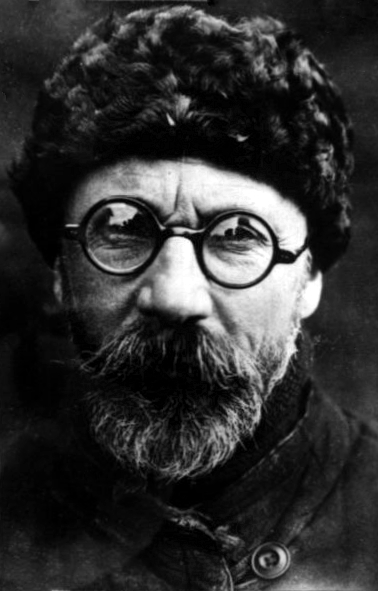

|

| Leonid Kulik |

Leonid Kulik got the Soviet government to fund his expedition, based partly on the chance that there would be a lot of meteoric iron that could contribute to the economy. It wasn't easy to get there. Local guides would only go so far -- they were afraid of the site. When Kulik finally arrived at the site, he was astounded to find, not only no meteor, but not even a crater. Instead, the area around the epicenter was covered with blasted trees, devoid of branches and standing straight up. The area extended about five miles in diameter.

Farther away than that, the trees were still burned, but had fallen, away from the center. The entire area comprised a rough "butterfly" shape, with a wingspan of 43 miles and a body length of 34 miles. The whole area covered about 830 square miles.

Kulik made multiple expeditions to the area over the next decade, and even took aerial photographs. The aerial photographs were burned in 1975 by the Chairman of the Committee on Meteorites. He claimed that they created a fire hazard, but a more likely explanation is that the scientists disliked anything that presented an unexplainable phenomenon. After all, they might be held responsible for not explaining it.

What Caused It?

|

| Photograph from the Kulik Expedition, May 1929. |

As far as we know, it's the largest meteor impact that's taken place on land in recorded history. Of course, if a similar impact had taken place over certain ocean regions, we might not have known about it.

It's not unusual for meteoroids to enter the Earth's atmosphere and explode. In fact, it happens every day. Larger explosions are more rare, but even so, the U. S. Air Force estimates that meteoroids as large as 30 feet in diameter -- creating an explosion about equivalent to the bomb dropped on Nagasaki -- explode in the upper atmosphere at least once a year. Explosions like Tunguska take place perhaps every 300 years.

Alternate Theories

|

| Kulik Expedition photograph, 1927. |

Another theory surmises that it could have been a comet containing a large pocket of deuterium, which had a nuclear fusion reaction and exploded, creating a natural H-bomb. It's also been posited that the event could have been caused by a black hole, a chunk of antimatter, or an explosion of natural gas within the Earth's crust.

It's even been suggested that the explosion could have been caused by Nikola Tesla, experimenting with the Wardenclyffe Tower, an early telecommunications project. And of course, there are always the aliens. The explosion could have been a spaceship accident, or a weapon going off, either as a threat, or to save us from a natural disaster.

No comments:

Post a Comment