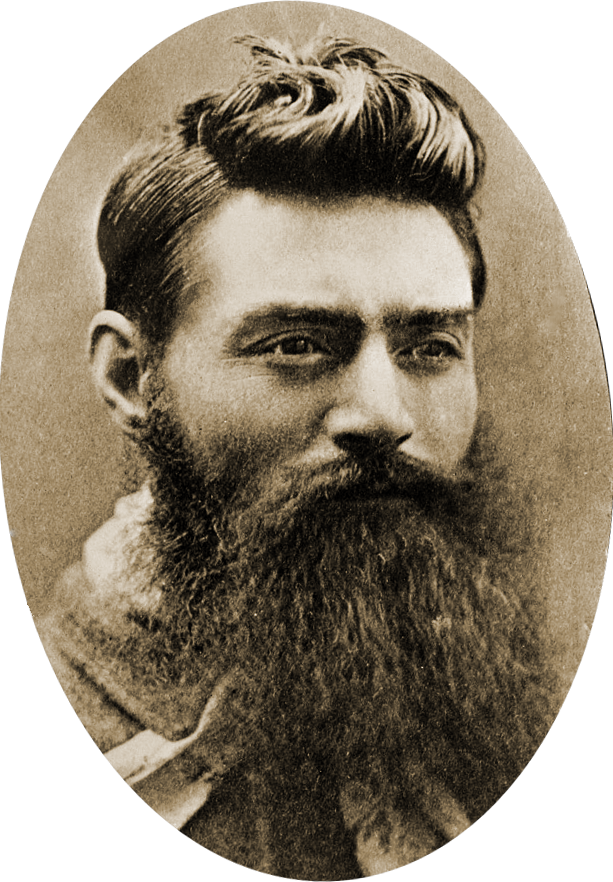

Ned Kelly Captured, 1880

|

| Ned Kelly, 1880 |

A Family Made for Trouble

After his release from prison, Red Kelly moved to Victoria, Australia, where he found work on a farm and married the farmer's daughter, Ellen. Red and Ellen had seven children who survived infancy. Ned was the oldest son.The whole Kelly family seemed to be constantly in trouble of some kind or another. Before Ned was proclaimed an outlaw, there were eighteen arrests against members of his immediate family. Only about half of them ended in conviction, and it's difficult to say now whether or not they were legitimate arrests or whether the Kelly family was a victim of police harassment. It certainly wasn't unknown for that to happen to Irish-Australians in the mid-19th century.

|

| He kept the green sash with him all his life. © bronzebrew/Wikimedia Commons |

Ned's Early Crimes

When he was 14, Ned had a run-in with a Chinese farmer named Ah Fook. Ah Fook claimed that the boy had robbed him. Ned's story was that Ah Fook had gotten into an altercation with Ned's sister, Annie. Whatever the truth was, Ned was arrested and spent ten days in jail before the charges were dismissed. The authorities called him a "juvenile bushranger." |

| Kelly at 15. |

The year after the Ah Fook incident found Ned arrested again. This time he was accused of being an accomplice of a well-know bushranger, Harry Power. Ned was held for a month, and then the charges were dismissed. Again, this could have been an example of the police harassment of his family. Or, it could be that Ned's family intimidated the witnesses.

He served time in 1870 for assaulting a hawker, and for delivering the hawker's wife a package containing a calf's testicles -- three months for each charge. It seemed to be a case of Ned getting mixed up in somebody else's argument. And then, as soon as he got out, he got tangled up in a mess involving a visitor, and a horse that ran away and was recaptured and turned out to be stolen. He got three years for that one.

In 1877, Ned was arrested for public drunkenness. He escaped, then turned himself in, and received only a fine. During the scuffle, however, Constable Lonigan grabbed him by the testicles and gave them a hard squeeze, an act that Ned never forgot. "If I ever shoot a man, Lonigan, it'll be you," Ned said.

The Fitzpatrick Affair

|

| Sister Kate. |

No one knew where Ned and Dan were -- it isn't even clear that they were actually in the vicinity at the time of the alleged crime. Despite a doctor's testimony that Fitzpatrick had been drunk when he treated him, and his inability to confirm that the man had even been shot, the judge accepted Fitzpatrick's uncorroborated story. Mrs. Kelly and the two associates who were there for the trial were found guilty of attempted murder. The judge said that if Ned were there, he would "give him 15 years."

Shootout at Stringybark

|

| Lonigan Kennedy, and Scanlon -- all killed by the Kelly Gang. |

Out looking for the Kellys were four men: Sergeant Kennedy, and Constables McIntyre, Scanlon, and Lonigan. Yes, the same Lonigan who had had Ned Kelly in his iron grip. They set up a camp at Stringybark Creek, then split up into two pairs. Kennedy and Scanlon went out to look for the Kellys, and McIntyre and Lonigan remained in camp.

Ned and Dan discovered them there, and decided their chances were better with two than with more. They had a plan to force them to surrender, and then take their guns and horses. McIntyre surrendered, but Lonigan tried to draw. Ned shot him dead. Now the boys were guilty of murder.

When Kennedy and Scanlon returned, they tried to get them to surrender, too. Neither did. They were both killed, as well.

The outrageous nature of these killings led to the Felons Apprehension Act which made the boys outlaws, and authorized anyone to shoot them on sight. No need for an arrest or a trial.

Euroa and Jerilderie

|

| Declared outlaws. |

In retaliation, police arrested all of the Kellys' known family, associates, and sympathizers. They held them for three months without charging them with any crime. The result of this abuse of authority was that the Kelly boys got even more support from the public.

In Jerilderie, the following February, the boys robbed another bank. This time, they first locked up the police officers and dressed in their uniforms. After mingling with the townspeople and buying them drinks, they removed about £2,414 from the bank. They also burned all the mortgage deeds that the bank held on local properties. It's easy to understand why the Kellys were quickly becoming folk heroes.

At about the same time as the Jerilderie heist, Ned Kelly wrote a lengthy letter (over 7,000 words), giving his account of his life and actions. He also dealt with the treatment of the Irish Catholics by the police and civilians. He intended the letter for publication, but it didn't make it into the press until 1930, when it was rediscovered and published by the Melbourne Herald.

The End of Ned Kelly

|

| Kelly's Last Stand. He couldn't really manage the gun. |

The Kelly gang next went to Glenrowan to take the bank there. The date was June 28, 1880. They held about 70 hostages, and ordered the railway tracks pulled up, since they were aware that the police were on their way to arrest them. They let one of the hostages go, however -- Thomas Curnow, the schoolmaster. Just why they released him we don't know, but it proved to be a big mistake. He flagged down the train, and prevented the train from being derailed. The inn where the men were holed up was soon under siege.

Bizarrely, the Kelly gang had decided to fashion their own armor. Each man had a suit that weighed about 96 pounds, and protected their torso and arms but left their legs unprotected. All four men also had helmets. They believed themselves impervious to bullets while wearing their armor. It is considered very possible that alcohol may have had something to do with their decisions.

The men wore gray cotton coats over the armor. The police had been informed that the men had armor, but hadn't believed it, and were mystified as to why their bullets had so little effect. "There is no use firing at Ned Kelly," one of them said. "He can't be hurt."

|

| Kelly's armor is now in the State Library of Victoria in Melbourne. © Chensiyuan/Wikimedia Commons |

Joe Byrne, the only member of the gang whose armor didn't include an apron in the front, was struck by a bullet in his femoral artery, and bled to death. Dan Kelly and Steve Hart were burned to death when the police set fire to the inn. Only Ned lived to stand trial.

Ned Kelly was tried for the murder of Constable Lonigan, found guilty, and sentenced to be death.

He was hanged on November 11, 1880 at Melbourne Gaol. In an effort to save him, over 30,000 people signed a petition asking that his life be spared.

No comments:

Post a Comment