Execution of Amelia Dyer, 1896

|

| Police photograph of Dyer, 1896 |

One solution for many women was the "baby farm." Infants were placed with a baby farmer, who either cared for the infant or attempted to place the child in an adoptive home. That was the theory, at least. The mother paid for the service, either as a weekly or monthly fee, or in a lump sum payment. Many mothers undoubtedly intended -- or at least hoped -- to reclaim the child when their situations improved.

As long as the baby farmer was receiving regular payments, the child was generally cared for. The problem arose when the baby farmer had received a lump sum to take care of the infant. There was really no incentive, in such a case, to keep the child alive.

Frequently, such babies died of starvation or inattention. Sometimes, their deaths were hurried on by the administration of "calmatives", alcohol or opiates. Godfrey's Cordial was a popular choice: at one gram of opium per two ounces of cordial, it kept the baby pretty quiet. The babies seldom died as a result of overdose, however. They were far more likely to simply lose interest in eating, and die of starvation or malnutrition.

Some mothers undoubtedly placed their baby in a farm knowing that the infant would die. Others may have feared for their child but had no other choice. Baby farmers often placed ads in newspapers. They were likely to offer to adopt a child and give it a good home, possibly in a country setting, for a price. A "one-off" payment could be steep, up to £80 for a wealthy family, or £50 for a father wanting to keep the occurrence hushed up. A working woman might pay £5 -- still a considerable sum for someone of her station.

Amelia Dyer took baby farming to the next level. It was too expensive, she thought, to keep the child until it died of starvation, and she had no intention of laying out good money for Godfrey's Cordial. She strangled them outright. She used white edging tape, the kind that was used in dressmaking. Later, after she had been apprehended, she told officials that the white tape "was how you could tell it was one of mine." The children did not die quickly -- Dyer said that she "used to like to watch them with the tape around their neck, but it was soon all over with them."

The case that hung Amelia Dyer was the murder of Doris Marmon. Doris was the infant daughter of Evelina Marmon, a 25-year-old barmaid who had given birth just two months earlier. She needed to have her daughter "adopted out", but she hoped in time to be able to reclaim her. She placed an ad in the paper, "Wanted, respectable woman to take young child." When it ran, she noted an ad right next to it in the "Miscellaneous" column: "Married couple with no family would adopt healthy child, nice country home. Terms, £10."

It sounded ideal. Quickly, Marmon wrote to "Mrs. Harding," who wrote back, telling her that she and her husband loved children, but were unable to have one of their own. They wanted nothing more than to adopt a lovely child and give it a loving home.

Marmon preferred to pay a weekly rate, but Mrs. Harding insisted on the "one-off", and Marmon finally agreed. When the woman came to collect the child, Marmon was surprised to find her older than expected, but she seemed a kindly and loving caretaker. A week later Mrs. Harding wrote to assure Marmon that all was well.

When Marmon wrote back, she received no answer. Mrs. Harding, of course, was Amelia Dyer, and she had quickly executed the child, and taken most of its clothes to the pawnbroker. The following day she acquired another child, but she was out of tape. She had to unwind it from Doris's neck to reuse it on little Harry Simmons. Both children were deposited in the Thames inside an old carpet bag stuffed with bricks.

On May 30, 1896, a bargeman on the Thames discovered the body of a baby girl, who was later identified as Mary Thames. The child had a white tape around her neck, and was wrapped in used wrapping paper. Under a microscope, the paper revealed an address, and the name "Mrs. Thomas." The address led them to Dyer, and a search of her home revealed white edging tape, receipts for newspaper advertisements, pawn shop receipts for children's clothing, and a pile of unanswered letters from mothers inquiring about their children. There was also a strong unpleasant odor in the home -- although no human remains were found there, they must have been left in the home for some time before being disposed of.

Dyer was arrested, along with her son-in-law. (Her daughter and son-in-law had apparently helped her with her crimes.) The Thames was dragged and more bodies were found, including the corpses of Doris Marmon and Harry Simmons. Evelina Marmon was able to identify her daughter's remains.

Dyer confessed, and absolved her daughter and son-in-law of any wrongdoing. She was apparently believed, as they were never charged. She was charged only with the death of Doris Marmon -- if she had been acquitted, she could then have been charged with additional deaths. She pleaded insanity, and indeed she had been committed to asylums twice in the past. Her commitments had usually taken place at times when it would have been convenient for her to disappear, and her insanity was generally considered to be faked. The jury took four and half minutes to find her guilty. She was executed on June 10, 1896, at 9:00 am.

No one knows exactly how many children Amelia Dyer killed. What is known is that she accepted at least 20 babies for placement in the last few months before her arrest. Some crime experts estimate that she may have committed as many as 400 murders in her long career.

Ballpoint Pen Patented by Laszlo Biro, 1943

|

| Advertisement for the Birome ©Roberto Fiadone/Wikimedia Commons |

Between 1907 and 1946, a number of "ball-point" inventions were patented. All relied on ink placed in a tube, which terminated in a rolling ball. The ball was coated with the ink in the tube, and then, as the ball rolled, deposited it on the paper. None of them worked very well. The ball couldn't deliver the ink evenly, and the writing tended to be very messy. None were commercial successes.

Laszlo Biro wasn't actually thinking of a ball-point when he started working on his pen. He was a newspaper editor, and he had noticed that the inks used in printing newspapers dried quickly. His first thought was to use that type of ink in a regular fountain pen, but he found that it was too thick to flow properly. His brother, a chemist, devised a new type of pen that could use it. Like the inventions of his predecessors, it was a ballpoint. What was different was that the Biro pen was pressurized, which kept the ink flowing consistently.

|

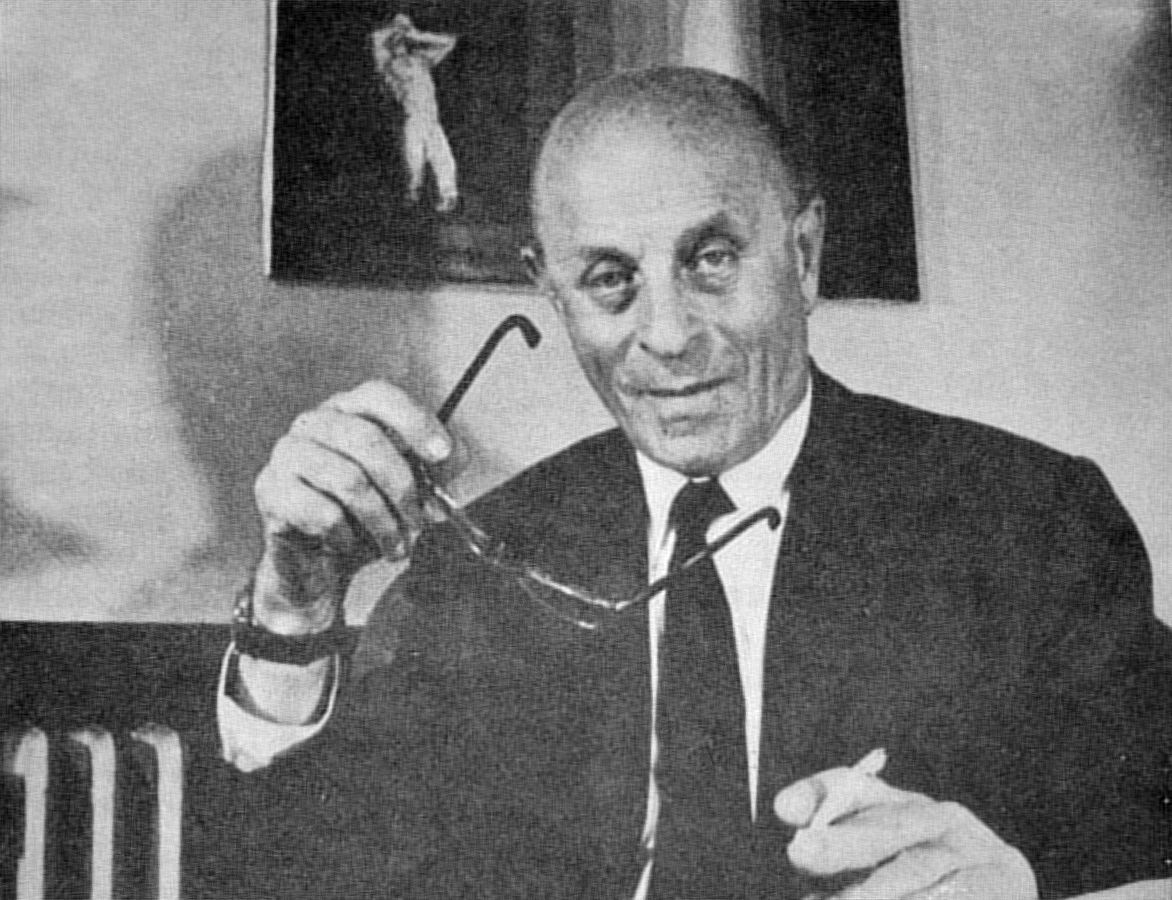

| László Bíró in 1978 |

The Biro pen was licensed in Great Britain, and Biro pens became standard for use by the RAF. In 1945 Eversharp, in conjunction with Eberhard Faber, licensed the pen for sale in the United States. Meanwhile, Milton Reynolds saw the pen for sale in Argentina and copied its design for his new Reynolds International Pen Company, which sold in the United States without licensing from Biro.

Ballpoint pens were first sold in the United States on October 29, 1945 at the Gimbels Department Store in New York City. They cost $9.75.

No comments:

Post a Comment