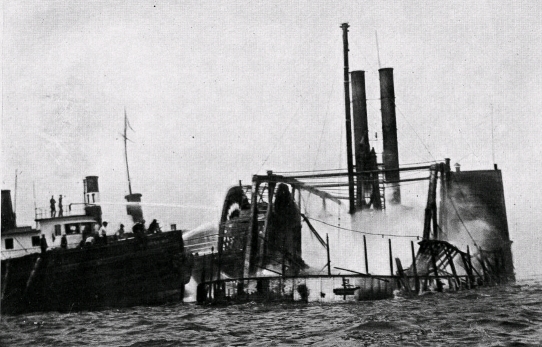

General Slocum Disaster, 1904

|

| The SS General Slocum |

The Slocum was a steam-powered paddle wheeler, about 13 years old, that was used as an excursion ship, taking passengers around New York City. It had been chartered by St. Mark's for the sum of $350. The group intended to sail up the East River and into Long Island Sound, ending up at Locust Grove, a popular picnic site on Long Island. The picnic was an annual event for the group. There were about 1400 passengers on board, most of them women and children.

The fire was first noted at 10:00, about a half hour after they had set out. A small boy ran to notify the captain, but he was not believed and was chased away. About ten minutes later the captain got word that the ship was on fire.

|

| The General Slocum on fire. |

The ship was only a few hundred feet from shore, but, rather than return, the captain set out for North Brother Island. Later, he would state that he had feared setting fire to the oil tanks and wooden buildings on the nearby site. This entailed the ship going headlong into the wind, which fanned the fire and made the blazes worse.

The paint on the ship was highly flammable, but that was not the only safety violation. Lifeboats were not only tied securely, but were actually wired in place and had been painted down.

Many of the passengers grabbed life preservers, only to have them fall apart in their hands. They had been made in 1891, and had been hanging above the deck of the Slocum for the past 13 years, completely exposed to the elements.

|

| Bringing out the bodies. |

The crew was at a complete loss. They had never had a fire drill and didn't know what to do. Some of them tried to put out the fire but the hoses fell apart in their hands -- they hadn't been maintained, either.

All told, there were an estimated 1,021 deaths. Some died from fire, some drowned, and some were killed by the paddle-wheel after they went over the side. Most of the passengers couldn't swim, and those few who could were hampered by their heavy clothing. Many of the dead bodies were unidentifiable.

A Federal Grand Jury investigated the accident, and although seven people were indicted, only the Captain was found guilty. (The other six were inspectors and officials of the steamship company.) He was convicted of criminal negligence, and sentenced to ten years imprisonment. He was paroled after three years and six months, and eventually pardoned by President Howard Taft.

The General Slocum disaster was the worst in New York's history until the September 11, 2001 attacks. It was also pretty much the end of Little Germany, which had been in decline for many years.

First Aviation Fatality, 1785

.jpg/615px-Early_flight_02562u_(8).jpg) |

| Deaths of Rozier & Romain -- memorial postcard. |

The next step was to be a manned flight, and King Louis XVI thought the passengers should be condemned criminals. De Rozier argued against it: surely an event that momentous should be performed by men of high standing. The king finally agreed that de Rozier and the Marquis d'Arlandes could be the first pilots.

This first manned flight lasted approximately 25 minutes, leaving from the Chateau de la Muette and landing on the outskirts of Paris, about five and half miles.

De Rozier made at least two flights after that before he decided that his next challenge would be to cross the English Channel. For this feat, a Montgolfier balloon would not be adequate -- they would need too much fuel to produce enough hot air to carry the vehicle. Instead, de Rozier designed a balloon that operated on a combination of hydrogen and hot air.

|

| Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier |

De Rozier set off with his flight companion, Pierre Romaine, on June 15, 1785. They made a little progress, and then the wind changed, blowing them back to France. They were 1500 feet above land when the balloon suddenly deflated and crashed. Both men died immediately.

De Rozier's fiancé died eight days after the crash, possibly by suicide. Louis XVI awarded a pension to de Rozier's family. An obelisk was erected in de Rozier's memory. The type of balloon he invented, combining hydrogen and hot air, is still called a Roziere balloon.

No comments:

Post a Comment