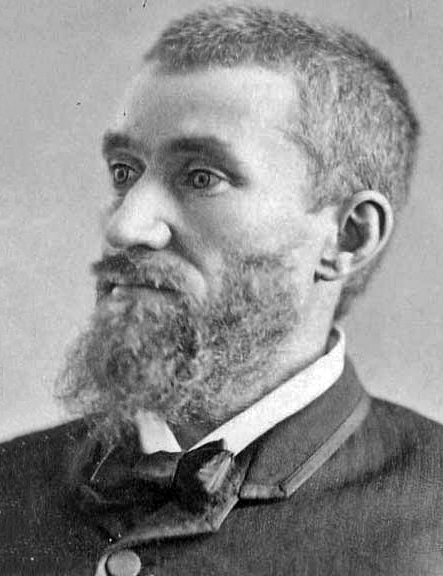

Charles Guiteau Shoots President Garfield, 1881

|

| Charles Guiteau: Never Quite Sane |

Charles Guiteau appears to have never been completely sane. He was born in Freeport, Illinois in 1841 and grew up there, except for a few years in Ulao, Wisconsin. When he was a young man, he inherited $1,000 from his grandfather, and decided to become a lawyer. He set off for Ann Arbor to study law at the University of Michigan.

Unable to pass the entrance exam, he enrolled at Ann Arbor High School to brush up on Latin and mathematics. Soon, however, he left school and, at his father's urging, went to New York to join the Oneida Community, a utopian group of which his father was a member.

The Oneida Community had been founded by John Humphrey Noyes in 1844. Noyes believed that the Second Coming had already occurred, in 70 AD. As a consequence, we were now living in a New Age. True Christians -- such as Noyes -- were already living in a state of perfection, and anything that their spirit led them to do was free of sin.

|

| At the free-love community of Oneida, he was known as "Charles Git-out". |

|

| Guiteau tried to sue Noyes. |

Guiteau left the Oneida group and tried to start a newspaper based on the community's religion, but was unsuccessful. He then returned to Oneida, left again, and this time filed lawsuits against Noyes. Guiteau's father was deeply embarrassed by his son, and wrote letters supporting Noyes's evaluation of Charles as irresponsible and insane.

Guiteau managed to pass the bar exam in Chicago and started a practice there. He had testimonials from nearly every influential family in the United States -- all forged, of course. Most of his business was concerned with bill collecting, and he wasn't a popular man with either his clients or the local judges.

He also lived for awhile in New York City, where he became known for skipping out on his debts. He had a string of boarding house landlords looking for him, and on some occasions his bills were paid by his brother, John. He also lived with his sister, Frances -- until he went after her with an axe he was using to chop wood. Frances attempted to have him committed, but he managed to evade her before she succeeded.

|

| Guiteau saw himself as a man of politics. |

It's not clear that Guiteau ever delivered his speech -- if he did, it was, at most, twice. Nevertheless, Guiteau had copies made which he passed out freely. He felt that his speech had been the deciding factor in Garfield's election, and expected to be rewarded for it. He preferred the ambassadorship to Vienna, but, when that was not forthcoming, he decided that Paris would be equally desirable.

Having written to Garfield and other political notables, Guiteau then decided to make a personal appeal. He arrived in Washington on March 5 (the day after the Presidential Inauguration), and actually managed to get into the White House and see Garfield. He left him a copy of his speech.

|

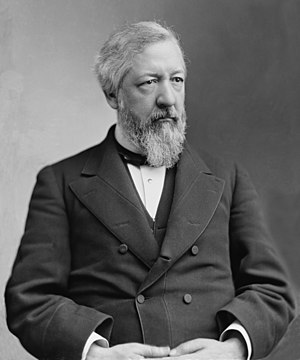

| "Never speak to me again of the Paris consulship as long as you live," said Secretary of State James Blaine. |

Guiteau had only the clothes on his back, and spent the next two months wandering around Washington. He became increasingly dirty and disheveled, but kept making the rounds, accosting various cabinet members and loitering in the White House waiting room. Finally, the Secretary of State, James G. Blaine, told him, "Never speak to me again of the Paris consulship as long as you live." On May 13th, he was banned from the White House waiting room.

This is when, according to Guiteau, God spoke to him. He borrowed $15 from an acquaintance and used it to buy a .44 Webley British Bulldog revolver. He spent an extra dollar for one with an ivory handle, because he believed that it would look good in a museum exhibit afterwards.

|

| Smithsonian photograph of Guiteau's gun. It has since been lost. |

|

| The Baltimore & Potomac Railroad Station |

Guiteau was waiting for him. He fired two shots. One grazed the President in the shoulder, and the other struck him in the back. The second shot lodged in his lumbar vertebra, missing the spinal cord. Guiteau was immediately arrested by an off-duty policeman who was so agitated that he forgot to take the perpetrator's gun until after he'd taken him to the police station.

Garfield was still conscious. Naturally, all those with him were extremely upset -- Lincoln was no doubt remembering his father's death, as well. He was taken back to the White House, and doctors did not expect him to last the night.

|

| Contemporary illustration of the shooting of Garfield. |

He did live the night, however. He didn't pass away for another 80 days, and then died more from his medical care than the actual injury. The doctors kept trying to locate the bullet, mostly by probing his wound with their dirty fingers. One of the doctors actually punctured his liver with his groping. Garfield became a victim to infection, fevers, and blood poisoning. His weight dropped from 200 pounds to 135. He suffered hallucinations. He developed bronchial pneumonia. Finally, on September 19th, Garfield died of a massive heart attack.

|

| Garfield might have lived if his doctors had left him alone. |

In particular, Guiteau objected strenuously to Scoville's assertion that Guiteau was insane. Guiteau insisted that, although he had been legally insane at the time of the shooting, he wasn't medically insane -- ever. He seemed delighted to be the center of so much attention, and waved gaily to his perceived "fans". He made plans for a lecture tour following his acquittal, and even considered running for President.

Guiteau was, of course, found guilty. He danced on his way to the gallows, smiling and waving at spectators and reporters. As his last request, he was allowed to recite a poem he had written, "I am Going to the Lordy." He had asked for orchestra accompaniment, but was denied.

I am going to the Lord, I am so glad,

I am going to the Lordy, I am so glad,

I am going to the Lordy,

Glory hallelujah! Glory hallelujah!

I am going to the Lordy.

I love the Lordy with all my soul,

Glory hallelujah!

And that is the reason I am going to the Lord,

Glory hallelujah! Glory hallelujah!

-- Charles Guiteau

No comments:

Post a Comment