The Bisbee Deportation of 1917

|

| Deportees being loaded into the cattle cars. |

Background

In 1917, about a fourth of all the copper produced in the United States was mined in the state of Arizona. One of the largest mining interests in the state was the Phelps Dodge Company, which owned the Copper Queen Mining Company, the largest employer in Bisbee. In addition to the mine, Phelps Dodge also held other business interests in Bisbee: the largest hotel, the hospital, the only department store, the library, and the Bisbee Daily Review, the town's only newspaper.Life in the mines was tough. Conditions were grueling, and even unsafe. Hours were long, the pay low, and living conditions in the camp were unhealthy. In addition, immigrant workers -- especially Mexican-Americans -- were routinely discriminated against by Caucasian supervisors.

The Bisbee miners had gotten little support from the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (IUMMSW.) But in 1917, a new union came to Bisbee -- the Industrial Workers of the World, also known as the IWW or the "Wobblies." By May 1917, they had signed up a few hundred workers and formed the Metal Mine Workers Union No. 800, a local of about 1,000 members, less than half of whom paid dues.

The new union presented management with a list of their demands. They included: an end to physical inspections (which were conducted to deter theft), no blasting while the men were still in the mine, a $6 per day shift rate, the assignment of two workers to each drilling machine, and an end to discrimination. Negotiations didn't take long. Management said no.

The Strike

|

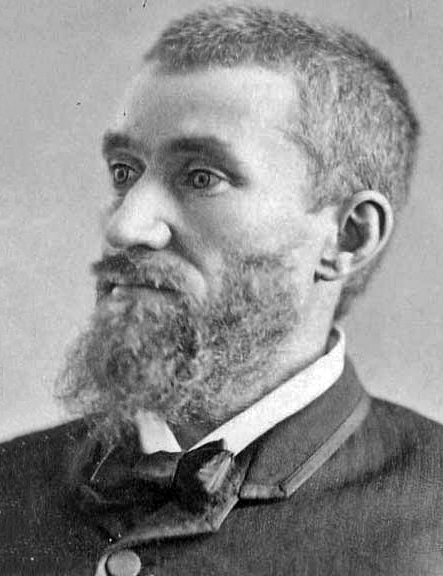

| "The whole thing appears to be pro-German and anti-American," said Sheriff Wheeler. That sure got the Feds attention. |

The strike was peaceful, there was no dispute about that. Nevertheless, the County Sheriff Harry Wheeler asked Governor Thomas Campbell to request federal troops to be sent in. (The state militia had previously been drafted into the federal service.) Wheeler interpreted the situation in a way guaranteed to get attention. "The whole thing appears to be pro-German and anti-American," he said. Remember, the United States had entered World War I less than three months earlier.

The Governor quickly requested troops, but President Woodrow Wilson turned down his request. Instead, he sent in George W. P. Hunt, the former Arizona Governor, to mediate.

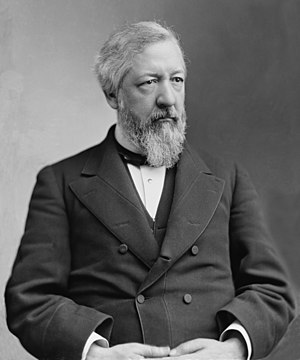

The president of Phelps Dodge was a man named Walter S. Douglas. He was well acquainted with the former Governor. The man was a political rival of his, and Douglas had had a lot to say about Hunt when, as Governor, he had refused to send in troops to stop earlier strikes. Douglas didn't have much faith in Hunt as mediator, so he began to take steps of his own. He immediately set up an organization of business leaders and other management-friendly residents known as the Citizens' Protective League. He also formed a Workmen's Loyalty League, made up of members of the IUMMSW.

Test Run in Jerome

Meanwhile, in the town of Jerome, Arizona, Phelps Dodge was having problems with mine workers as well. With the assistance of their local sheriff, the business leaders and IUMMSW loyalists in Jerome rounded up 67 striking miners and sent them to Needles, California. It was, apparently, a "test drive" for what was to happen in Bisbee.

The Deportation

|

| Deportees at the ballfield. Those are armed posse members in the infield. |

Each of the deputies had a list of the striking workers. Each also wore a white armband, to distinguish him from the strikers. Besides the striking workers, they arrested any man who refused to work in the mines, anyone who had ever supported the IWW, and even a few grocers. (The deputies helped themselves to money in the till and merchandise while they were at it.) The deputies were armed, but only two men died in the round-up. One was a deputy who was shot when a miner fired through the door. The other was the miner, who was shot dead by several other deputies moments after.

It took only about an hour for the posse to round up about 2000 men. They marched them about two miles to the local ballpark and then held them there. Men who did not belong to the IWW were allowed to leave, -- if they agreed to go back to work.

There were 1,286 strikers left when the train arrived at 11:00 am. The men were forced onto cattle cars, most of which had floors covered with several inches of manure. The cars were so crowded that the doors couldn't be closed. The strikers had not received water since their arrest.

There was no report of the deportation to the outside world. Phelps Dodge had taken control of the local telephone lines, as well as the telegraph office.

The train was bound for Columbus, New Mexico, but officials there wouldn't allow the strikers to be left there. They were taken instead to Hermanas, New Mexico, a nearby station. They were abandoned there, and left to fend for themselves.

The Governor of New Mexico, Washington Ellsworth Lindsey, instructed the local sheriff to treat the men humanely, and to feed them. He also contacted President Wilson and asked for instructions. Wilson sent federal troops to take the strikers to Columbus, where there was a federal refugee camp for Mexicans escaping the conflict between the U.S. Army and Mexico's Pancho Villa. They were allowed to stay there until September 17.

Meanwhile, Back at Bisbee

The Citizen's Protective League was running a tight ship in Bisbee. They collected residents and interrogated them about their beliefs -- about unions, politics, the war, and the draft. Sheriff Wheeler set guards at the entrances to the town, and no one was allowed to enter or leave without a "passport." Many more residents were ordered to leave Bisbee.Amazingly, even national press coverage of the deportation tended to be less than sympathetic to the miners. The prevailing opinion seemed to be that the strikers had "gotten what they deserved." Some of the more liberal papers thought that the deportation had been too much -- the men should simply have been arrested for vagrancy and imprisoned. Former President Theodore Roosevelt said, "...no human being in his senses doubts that the men deported from Bisbee were bent on destruction and murder."

Deported citizens applied to President Wilson for help. He appointed a commission, headed by his Secretary of Labor, to investigate. On November 17, 1917, they announced, "The deportation was wholly illegal and without authority, either State or Federal."

The Aftermath

In May, 1918, 21 men -- various executives of the three mining companies (including Walter Douglas), elected leaders, and law enforcement officials -- were charged by the U.S. Department of Justice. (Sheriff Wheeler was not among them, because he was serving in France in the war effort.) The case was dismissed on the basis that there had been no federal laws broken. An appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, United States v. Wheeler, found that the federal government did not have the authority to protect the rights of the deportees, and that the individual states retained the right to deal with questions of ingress and egress.Arizona authorities never instituted legal proceedings against the deporters. A few workers filed civil suits, but after the first case against the strikers -- the jury found that the deportation was sound public policy -- most of the other cases disappeared.

The main consequence of the Bisbee deportation was the enactment of various laws -- such as the Sedition Act of 1918 -- to empower the federal government to deal with speech and actions that could be construed as disloyal to the United States. If such laws had existed in 1917, it was argued, the involvement of private citizens would not have been necessary to deport the striking minors.

.jpg/1077px-PAUL_DELAROCHE_-_Ejecuci%C3%B3n_de_Lady_Jane_Grey_(National_Gallery_de_Londres%2C_1834).jpg)

01.jpg/751px-Cromwell%2CThomas(1EEssex)01.jpg)

.jpg/569px-Anton_Karas_(1906-1985).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)