Law Day

Many, many years ago, when I was in high school, our school used to observe Law Day on May 1st. The holiday was ostensibly about how lucky we were to live in a nation that was ruled by law, but it was really a reaction to the May Day celebrations of the rest of the world honoring the Worker and the Labor Movement. The Soviet Union celebrated May Day; we would celebrate Law Day.Our "celebration" consisted of long assemblies of the entire student body in which we were preached to about how lucky we were to be Americans. There wasn't anything particularly wrong with the message, but propaganda is propaganda, and it didn't sit very well with restless, opinionated teenagers. I think they abandoned the assemblies after a couple of years.

I don't want you to think that I was a budding Commie. I was perfectly satisfied to be an American, and I had a good deal of the general distrust of the USSR that was so prevalent during those years. I also thought the Russian people were probably, well, people. Pretty much like us. And they did have some humdinger novelists to their credit.

More to the point, I thought that May Day was already a perfectly fine holiday. Maypoles, May Baskets secretly left on doorsteps, the Fairy Queen bathing in dewdrops under the hawthorn tree. That sort of thing.

On the other hand, it might have been Loyalty Day we were celebrating -- I don't really remember. Law Day and Loyalty Day came into being at about the same time, in 1958 under the administration of President Eisenhower. Earlier still, beginning in 1921, it was known as "Americanization Day." I'm not quite sure why our school system started celebrating it in the mid-60's. Maybe it was a delayed reaction to the Bay of Pigs. Regardless of what you call it, the theme of the day was "Let's all give thanks that we're not godless communists."

The United States is one of the few major countries in the world that doesn't celebrate International Workers' Day on May 1st. (We have our own Labor Day, of course, at the end of summer.) In part, this is to differentiate ourselves from the communist/socialist/leftist organizations and countries that do celebrate it. There's also another reason for not celebrating it on May 1st that I'll get to in the next section.

|

| International Workers Day, 1912, in New York |

International Workers' Day

The creation of International Workers' Day goes back to 1889. In that year, the Second International, an early coalition of socialist and labor parties, met in Paris on the centennial anniversary of the French Revolution. The Second International called for demonstrations all over the world on May 1, 1890, the fourth anniversary of the Haymarket Affair.The Haymarket Affair was a series of events that took place in Chicago over a period of several days beginning on May 1st. May 1st had earlier been designated by the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions as the day by which an eight-hour day would become the standard. When this didn't happen, protests and strikes took place all over the country.

.jpg) |

| Mathias Degan, killed by the bomb |

One of the centers of unrest was the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company. McCormick workers were particularly assertive about reaching the eight-hour workday, and were still smarting from run-ins they had had with the Pinkerton security force the previous year. Strikebreakers were brought in by management, guarded by about 400 police officers to replace the striking workers, but about half of the "scabs" joined the strikers.

A rally was held outside the McCormick plant on May 3rd. The event was nonviolent initially, but when the workday ended the strikebreakers and strikers got into face-to-face altercations. Police fired into the crowd, killing at least two workers, and perhaps as many as six.

Anarchists quickly organized a rally for the following day. They believed that the police were murdering workers in order to protect business interests, and called for the workers to fight back. An early version of the flier asked the workers to arm themselves, but August Spies, one of the organizers, refused to speak unless the flier was revised. New fliers were distributed.

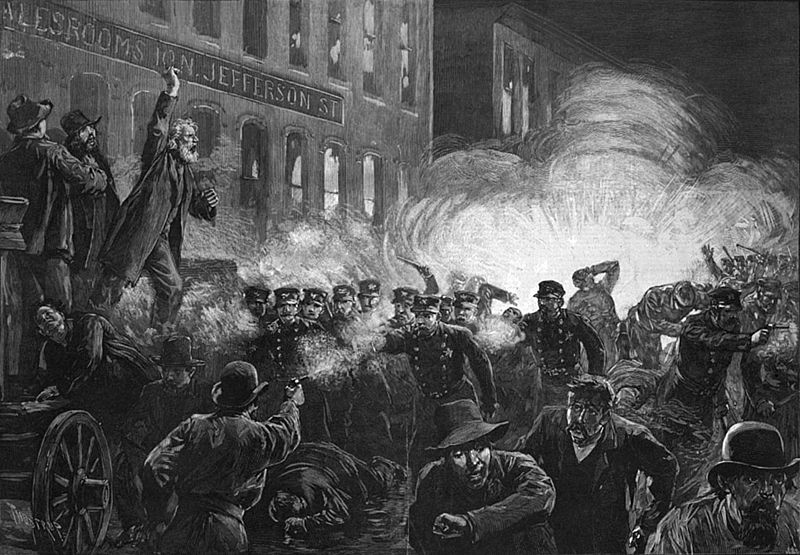

The rally was peaceful enough at the outset. Spies began by clarifying that the rally was not meant to incite violence. A large number of policemen stood nearby, under orders not to intervene. The mayor himself watched for awhile, but left early, apparently not deeming it a significant event.

All that changed when the last speaker finished. Police ordered the crowd to disperse, and started marching in formation toward the speakers' platform. At this point, somebody threw a pipe bomb, which killed one of the policemen, Mathias J. Degan, immediately. The police began firing, mostly at each other.

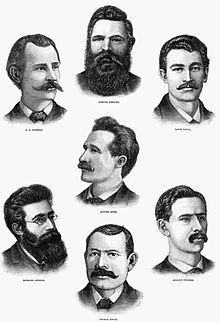

|

| The Haymarket Martyrs. These 7 men were sentenced to die. |

No one ever discovered who threw the pipe bomb. Eight men, all anarchist organizers of the rally, were charged with Degan's murder, although witnesses verified that none of the eight threw the bomb. Five of the eight were German immigrants, two were born in the United States, and one was born in England. The prosecution's argument was that none of the eight had discouraged the man from throwing the bomb, and thus were equally responsible. Two other men were indicted, but never charged, one because he turned state's evidence, and the other because he fled the country. All eight were found guilty. One man -- Oscar Neebe -- was sentenced to 15 years imprisonment. The other seven all received death sentences.

The sentence was appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court, and then to the US Supreme Court. The US Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

The governor commuted the sentences of two of the convicted men -- Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab -- to life in prison. Another -- Louis Lingg -- committed suicide in his cell the night before his scheduled execution with a cigar bomb (a cigar with a dynamite blasting cap). It blew half of his face off but he lived for six hours afterwards.

The other four men -- August Spies, Albert Parsons, Adolph Fischer, and George Engel -- were executed by hanging. They did not die immediately on the drop, but strangled slowly, taking several minutes.

The trial of the anarchists was considered by many to be a complete travesty of justice. The jury selection was accomplished by a specially appointed bailiff. One of the jury members was a relative of a policeman who had died in the fracas. Many workers believed that a Pinkerton agent had thrown the bomb. Five and a half years later, the governor pardoned the Fielden, Neebe, and Schwab, believing that all eight anarchists were innocent, and that the reason for the riot was the city's failure to hold the Pinkertons responsible for the previous shootings. He was not reelected.

This, then, is the background for the day that is celebrated in a large part of the world as International Workers' Day. The United States celebrates Labor Day in September because that was the day suggested and promoted by the Central Labor Union and the Knights of Labor. In 1887, one year after the riots and three years before the first celebration of the May 1st Labor holiday, President Grover Cleveland threw his weight behind the September celebration, fearing that a May celebration would provide too much of an opportunity to celebrate the riots.

In 1955, the Roman Catholic Church designated May 1st as the Feast Day of "St. Joseph the Worker." St. Joseph, the husband of the Virgin Mary, is, among other things, the patron saint of workers, craftsmen, immigrants, and those who fight communism.

|

| The Haymarket Riot |

No comments:

Post a Comment